Posting stories of my childhood memories on Washburn Island, Lake Scugog is one of my interests. For 60 years, from the 1930s to 1990s there were at varying times five family cottages on the island. We lost my cousin Ronnie Baker in a tragic accident on Washburn Island in 1957. This first story introduces you to Ronnie. The legend at the bottom of the page locates the Baker cottage beside The Point on the west side of Wakeford Rd.

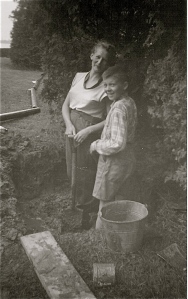

Ronnie standing beside Aunt May Hamlett c. 1954

Cow Pies

Ronnie’s voice, high-pitched and excited, says, “Percy’s got a bloody bull at the farm!”

“You said ‘bloody’,” says seven-year-old cousin Phyllis.

Ronnie grins, and steps out a crisp military turn, a skinny eleven-year-old with bare feet pressed into the sandy ruts to Percy’s farm. Five girl cousins straggle out from under a cool cedar canopy to form ranks, awaiting orders.

Ronnie straightens his boney shoulders, flattens a stripped cedar walking stick under a bent left arm, and announces, “Right turn into the woods. Follow me, men.” Then he marches forward to the humming of the Colonel Bogey March, an inspirational march created in WWI to inspire British military fortitude.

Sadly today I know the same music is a popular theme song for the movie The Bridge On the River Kwai released in 195–but Ronnie will die before it’s release. The version Ronnie hums in 1954 he learned from his father’s collection of long-playing records ordered from all over the world. Ronnie’s not allowed to touch the records or the gramophone, but Uncle Harrie makes sure his kids listen to expensive international recordings of marches, operas, and classical music.

From left at the Baker Cottage: with back to the camera, Aunt Nora (or possibly my mum), Viv Burrows, Aunt May Hamlett, seated is me, my father jesting in a chef’s get-up, cousin Terry, her sister Phyllis, Ronnie’s sister Susie, my sisters, Maeve and Barb.

A file of girl-soldiers set off after Ronnie, ages ranging from six to eleven. Cedar boughs slap and scratch, but we happily troop behind our leader–and the only boy. When Phyllis won’t let go of his swear word and threatens to tell on him he pivots and commands, “no God-damn insubordination.”

“Twice. I’m telling,” she says.

Noisy chipmunks chase in the damp soil and kick up dried cedar droppings. My sister Barb, who is six months older than Ronnie, ranks next in the chain of command, but only comes to real power when Ronnie chooses to hang around with the uncles and leaves the girls to plan their own play.

“A God-damn bloody bull,” he says to Barb as she dodges low-slung cedar branches.

“Don’t swear,” she says, looking to see if the little ones have heard him swear again — and we have.

Mosquitoes attack exposed skin, made sweaty from humidity locked inside the forest. We swat at them and scratch tiny raised bumps on necks and legs.

“Cow pies,” Ronnie shrills, stopping beside a circular splat of brown muck.

Squeamish girls break ranks behind him, peering around each other to see the cow pies, erupting “Eeewww” sounds, fingers clamped to noses.

“Fresh, too,” he says, grinning at my sister Barb, his best pal.

She wrinkles her nose and skirts the circle, saying, “C’mon, let’s go.”

“Who’s gonna jump in?” Ronnie challenges.

I’m second youngest of the gawking girls sweating and swatting beside the cow pies, but I know what might come next and I’m not budging.

“No takers?” he scoffs, looking at the faces of disbelievers. “Chickens.”

Ronnie pumps his arms, bends his knees – “One … two … three …” He lifts a perfect barefoot, standing-long-jump smack in the center of a smelly brown cow pie.

Little girls run in all directions, squealing and looking back at the laughing boy who has splashes of pooh coating feet and ankles.

“That was stupid,” said Barb, but she laughs because he laughs — at least he laughs until he has a hard time scraping off the filth.

It’s one of the first times I remember wishing I was a boy. I wished Mum wouldn’t yell at me if she heard that I jumped in pooh. I wished I were brave and naughty and laughing at pooh squishing through my toes.

We detour long enough for Ronnie to wash his feet in the warm shallows of the lake. No longer, soldiers, we tramp out of the trees onto the sandy road to the farm.

Phyllis told the adults about Ronnie’s swearing when we got back. As soon as we’d blurted out about the bull sighting, Ronnie’s cow-pie-stomp loomed large in our tale too. The bull sighting got a lot more attention from our parents.

“Was he in the barn? Tied up, or chained up? Did Percy let you in the barn? Don’t go there again.”

But the disgusting act of cow-pie-jumping didn’t seem to diminish Ronnie in anyone’s eyes. Ronnie good-naturedly chirped back at the teasing uncles who called him, ‘Simpleton, and Clodhopper.’

As the years pass, I’m aware of how much everyone liked Ronnie, my Dad especially. I can tell by the way he teases Ronnie about being a muscle man, even when at thirteen the boy is slight but wiry. Step-N-Fetch-It, Dad calls him. Ronnie responds by retrieving tools and lumber, eager to please. He hangs around the jocular company of uncles, telling jokes, listening to their stories. And he charms the aunts by helping set up tea under the elm tree in the front yard, or minds the little ones near the shore.

Ronnie is first to have a radio of his own. I don’t understand then why he and Barb choose to go into Aunt Nora’s cottage on a sunny day just to hover close to static, listening for rock ‘n roll tunes, like Elvis Presley’s Hound Dog. But the two are past the age of making clay ashtrays at the shoreline with the younger kids.

Until July of 1957, there was a sense of being safe at Washburn Island, like growing up inside a cocoon. Summer breezes and sheets of blue sky lulled us to complacency. We can’t know that soon a change in the weather will smash the cocoon to the ground and change our innocent reflections of childhood on the island.